- Nederlands

- English

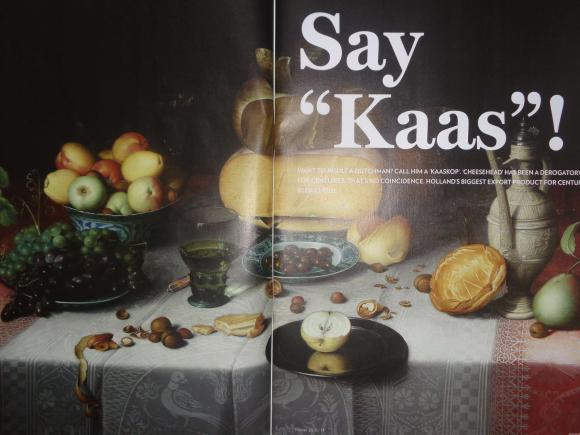

Winter 2014: Say "Kaas"

Say “Kaas”! Text Benjamin RobertsPhotography Benjamin Roberts, Reypenaer, RijksmuseumThe golden, round-shaped Gouda and red paraffin wax-wrapped Edam have become synonymous with the Netherlands, and the Dutch. Believe it or not, the export of cheeses to the rest of Europe was born out of sheer necessity. During the Middle Ages, the Netherlands was a poor country when it came to natural resources. There were no precious metals and minerals to be traded for other products. Besides wind and water, the only asset the tiny country on the North Sea had, were its rich green pastures doted with Frisian and Dutch Belted Cows. Cheese quickly became a trade product, or the gold bullion with the countries of the Baltic Sea, which were rich in lumber and grain. With Gouda and Edam, lumber and wheat were purchased to build canal houses and bake bread. Today with 1.5 million dairy cows in the Netherlands, cheese is still the gold bullion of the Dutch economy. In 2010, 752 million kilos (1.657 trillion pounds) of cheese were produced, of which 576 kilos were exported, and nearly half to Germany. Is it “gow-da” or “goo-da”?Gouda is the most widely known Dutch cheese. The cheese – recognised by its yellow, wheel-like shape – got its name from the city of Gouda where cheeses were weighed and traded. There were never any cheeses produced in the town of Gouda, it was only a market town where farmers came and sold their cheeses. Today, foreigners visiting the Netherlands might run into trouble being understood if they ask for ‘goo-da’. The correct pronunciation is ‘gow-da’ with a guttural ‘g’, similar to the Spanish ‘g’. After one American tourist was explained the difference in pronunciation, he comically quipped back in a pseudo Italian accent: “I don’t know gow-da say it, but it’s goo-da to me.” According to Guillaume Pieters, cheese master or fromager of Reypenaer Cheese Store on Singel 182 in Amsterdam, “Gouda cheese is not based on any particular taste or smell. The name Gouda only signifies the round, wheel-like shape. The name Edam signifies the cannon-like form.” In 2010, the Dutch Dairy Board won a seven-year campaign with the European Union to have the two classic Dutch cheeses given a protected status. Now, only cheeses with the label ‘Dutch Gouda’ or ‘Dutch Edam’ are real Dutch cheeses. Before, labels with Dutch Gouda were produced as far away as New Zealand and Canada, and were still labelled Dutch Gouda or Edam. Thumping cheeseFive generations of the Van den Wijngaard family have been ripening Reypenaer cheeses in their warehouse in the small town of Woerden, better known as the geographical heart of Holland. For more than a hundred years, the family has been ‘thumping’ and turning wheels of cheese twice a week like clockwork. Seasoned fromagers can easily detect if a cheese wheel has accumulated gas during the fermentation process by thumping. When there are pockets of gas locked in a cheese, it turns into Swiss cheese (i.e., leaving holes behind). And the turning and rotating of cheeses, ensures the fat content is evenly distributed throughout the entire wheel. Men who ripen cheese have to be strong because each wheel can weight up to 17 kilos in the beginning. By the time the average cheese has matured, it weights from 12 to 14 kilos, as the cheese releases water during the maturing process. 60-minute tasting courseAt Reypenaer Cheese Store, visitors can sample their cheeses during a 60-minute tasting course. Laymen are introduced to six cheeses, ranging from cheeses made from goat or cow milk, and aged four months to three years. Reypenaer’s dark-yellow belegen kaas is considered to be the most flavourful. From this mildly aged Gouda cheese, a slight woody taste comes to the palette. Pieters adds: “That should be no surprise, considering that the interior of the warehouse in Woerden is made of pine.” Reypenaer cheeses are also naturally matured; the temperature is cooled by opening the hatches of the warehouse. The pièce de résistance from its assortment is called Reypenaer V.S.O.P (Very Special Old Product), a two-year-old cheese made from cow’s milk. On the tongue, it has a grainy and dry consistency, and a rich, earthy flavour. Pieters explains: “80% of the taste comes from ageing.” When a ruby port is immediately sipped afterwards, the taste buds are overrun with a distinctively dark chocolate flavour. Cheese sandwich, pleaseOf the 18 kilos (41 pounds) of cheese that are individually consumed in the Netherlands annually, the Dutch prefer their Gouda to be belegen, a young cheese that has ripened after 20 weeks. It has a lactic taste; it’s clean, wholesome and milky, and it’s soft texture makes it perfect for sandwiches, which is the way most Dutch eat cheese. Cheese on buttered bread is a main staple of the Dutch cuisine and lunches in general. Expats in the Netherlands are often amazed at how Dutch employees prefer to lunch – each and every day – with their homemade sandwiches made with Gouda cheese. TurophilesWhen it comes to buying cheese, Amsterdam locals swear that De Kaaskamer van Amsterdam or ‘the cheese room of Amsterdam’, is the best place in town. In the tiny shop (Runstraat 7) nestled in the Nine Little Streets shopping district, 300 to 400 cheeses are stacked from ceiling to floor. According to manager Tim van Laar, the majority of De Kaaskamer’s cheeses are farmstead, and produced by small dairy farmers that have a passion for cheese-making. He emphasises, that all four employees that work in the shop are turophiles, “we love cheese”. Van Laar adds: “Every time a farmer comes up with a new cheese, we are critical to taste it, because we are continuously looking for the most delicious one. That’s our challenge.” A lot of aromaFarmer cheeses are made with raw milk, and still contain bacteria that enhances the flavour. Van Laar explains: “Most factory-produced and aged cheeses have a smooth, rubbery texture with a bland taste. The flavour or farmstead cheese, on the contrary, overwhelms the palette with a creamy flavour and barnyard aroma.” They usually have a grainy and silt-like texture from the particles of lactose because the milk has not been pasteurised like factory-produced cheeses. Van Laar continues: “The taste, well, that goes without saying: the slightly aged jong belegen (10 weeks old) and belegen (20 weeks old) are rich and creamy. And the more matured extra belegen (30 weeks old) with its orange colour has a nutty flavour.” Already since the 17th century when Holland established its trade with the East Indies and Spice Islands, cheese-makers have experimented with different flavours. An all-time favourite is the Frisian Nagelkaas, a dark-orange cheese speckled with brown stars, that is matured at three years and seasoned with cloves. Leidse Komijnkaas is a lighter cheese, seasoned with cumin seeds, and has a lot of aroma. Kaaskop! (Cheesehead!)As people become more health-conscious and develop their palette, local cheese made from raw milk is becoming more popular. An influential force in the use of raw milk for cheese-making is the Slow Food Movement, which hopes to retrieve many traditional cheeses that have disappeared after factory-made cheeses started standardising taste buds in the early 20th century. From its selection of Slow Food cheeses, De Kaaskamer has an excellent Boeren opleg cheese, aged from 18 to 24 months. It also gets its extra flavour from being made in wooden tubs, which has been the traditional way of making cheese in Holland for centuries. According to rumour, Dutch farmers used traditional cheese tubs during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) when they did not have other any protective headgear, again in necessity. When French soldiers saw a group of armed Dutch farmers approaching them wearing cheese tubs on their heads, they amusingly referred to them as ‘cheeseheads’. The ‘kaaskop’ was born.

You always wanted to know more about cheese, but you never dared to ask? Here is your chance, at Reypenaer, in the centre of Amsterdam.